The Punctuation of History

Anthony Blake

This is another extract from his work in progress on Higher Intelligence and relates to our explorations of ancient history such as the recent trip into ‘Enchanted Albion’

About 70,000 years ago, a small population of perhaps 2,000 people barely surviving in Africa were all that were of human kind. Now there are six billion of us spread throughout the Earth and we are reshaping the very fabric of the planet. The saga of human kind extends backwards and forwards from that hazardous moment in prehistory. We try to make sense of it by finding a shape in the flux of events, just as we might in regard of our own lives. The implication of a shape is that there is some design – though not necessarily a designer.

A shape of history can be looked at as analogous to the punctuation of a sentence and the way sentences are combined to tell a story. Punctuation is mentioned in particular because it means the operation of separating moments that help define the meaning of the sentence, as in phrasing it in articulate parts as well as separating words by spaces. The purely temporal line of time along which we display dates as arbitrary markers can be contrasted with a kind of time in which moments are intrinsically distinguished because they concentrate meaning. This has always been in the concept of time, since the root of this word relates to the idea of a ‘cut’ or mark. History is punctuated by critical events; but in a more extreme sense, time itself may be structured in significant ways.

The idea of time itself as having a structure has been suggested by Whitehead, who spoke of periods of more or less ‘novelty’. His organic view of the cosmos would inevitably entail such a structure, because the organic paradigm centres itself on wholes that are related, rather than any bland continuum containing atomic particles moving by external forces. A selective quote from Whitehead here will convey the depth of his distinction between the time of measurement and the time of ‘creative advance’:

It is not the usual way in which we think of the Universe. We think of one necessary time-system and one necessary (i.e., instantaneous) space. According to the new theory, there are an indefinite number of discordant time-series and an indefinite number of distinct (i.e., instantaneous) spaces. Any correlated pair, a time-system and space-system, will do in which to fit our description of the Universe. We find that under given conditions our measurements are necessarily made in some one pair which together form our natural measure-system. The difficulty as to discordant time-systems is partly solved by distinguishing between what I call the creative advance of nature, which is not properly serial at all, and any one time-series. We habitually muddle together this creative advance, which we experience and know as the perpetual transition of nature into novelty, with the single time-series which we naturally employ for measurement. The various time-series each measure some aspect of the creative advance, and the whole bundle of them express all the properties which are measurable.

The description says that the organic creative time of advance is not serial. This needs to be born in mind when we try to lay out a time line with punctuation as a single structure; because such a punctuated line is barely capable of representing the organic nature of advance. However, in our every day representation of our own kind of intentional achievements, this is precisely what we do. It is common to depict such achievements as proceeding through a series of steps. Such steps come one after the other, in a certain order, implying at least that the successive ones require the attainment of previous ones. The practical concern is whether we have done enough of one kind of thing to move onto another kind of thing, because of we have not then the enterprise will fail. This renders each step as a complete thing in its own terms.

The depiction of steps to attain a goal may not be entirely amiss, once the quasi-independent nature of each step is taken into account. A larger significance is that the ordered sequence of steps forms a whole with superordinate properties. This allows for the series of steps to entail an inherent structure in which some at least of the steps serve as an integration of previous ones, reflecting the properties of the whole. Using a now common word, the series may have an implicit ‘fractal’ form.

The succession of steps, then, need not be entirely a matter of just one thing after another. The idea of minor steps of integration may then be treated as a way of ‘bundling’ different time-series together – to use Whitehead’s words – in an organic sense. This makes possible the arising of key events or moments in which a critical transition may be made.

The esoteric philosopher Gurdjieff made much of the idea of a series of steps to accomplish a goal in which there were critical – and consequently hazardous – moments. Following a traditional symbolism, he asserted that any true completing process took place in seven steps and contained two such moments. The first three steps required a step of integration and then, consequently, the next four steps required another. His model was that of the major diatonic scale of the octave, resting on the metaphor of moving from lower to higher ‘do’ through a series of intervals. The depiction here uses simple brackets to focus attention on the structure of groupings involved:

(((A B C) (D E F G)) H)

In Gurdjieff’s exposition, the critical transitions were to be marked in some significant way: something would come in that was not there before.

Seeking a physical analogy, we might think of a chemical process in which each step was metastable (that is, could easily be destabilised) with the exception of the critical transitions, which achieved some relative permanence. If these critical steps were not made, then the whole process would go astray and end at some deviation from the intended goal. The means of making the critical transitions may equally well be taken as intrinsic to the developing process – achieving critical mass or intensity for example – or to some incursion. Pragmatic thinking would favour both as at least possible.

It is easy to project such a scheme on anything we might look at retrospectively. We started with the critical moment 70,000 years ago and might well take this to signify the first critical transition: a distinct isolated group of sapiens with the potential of making radical developments. Why they were so capable we do not know. The time period before can range back a hundred thousand years to the very beginnings of our modern species. We could also speculate that the second critical transition took place about 12,000 years ago with the arising of agriculture and expanding group culture. This would be to detach ourselves from the Eurocentric attachment to the extraordinary burst of creativity 30,000 – 15,000 years ago evidenced by the art we all stand in awe of. In terms of present knowledge, we just do not know what happened in the interval before the Neolithic revolution.

When we come closer to our historical times, we encounter the phenomenon of humans marking their own time by making constructions of great intelligence and import. In Gobbleki Tekke in Turkey, there stand stone circles and sculptures dating back perhaps 12,000 years and some have taken these constructions as a deliberate act to initiate a new era: the construction of such monuments would have required the gathering of unprecedented numbers of people requiring food and shelter not previously possible. In later times, massive monuments have been read as defining their times and even sending messages into the future.

In looking back over human history we are not simply surveying a sequence of material events but also, increasingly, a consciousness of what events might mean. We might put it like this: as we look back to them, they are looking forward to us. At the very least, they are interpreting their times as they lived them as much as we are retrospectively. The situation is akin to anthropologists looking at an aboriginal culture. As far as we can tell, as soon as humans acquired language and collective memory, they were seeking out the meaning of their existence and asking the perennial questions: Where have we come from? Where are we going?

At the very least, we can expect to find some – often profound – equivalent to that old Second War graffiti ‘ Kilroy was here’. We expect kings and rulers to set out stele proclaiming their glories but there are also ‘marks’ made in the fabric of time that signify some conscious awareness and interpretation of history itself.

This is a serious matter in the realm of human history and prehistory, because we have come to suspect that humans living even a hundred thousand years were much like us and we have no right to project on them the image of being ‘primitive’. At the same time, we may also suspect that how people responded to their times – and to themselves – was subject to change. After all, the most sensible general description of the time of human kind is that it is the history of mind. Mind is the epitome of creative advance (allowing for its concomitants of decay and deviation, too).

The history of mind can be seen in many ways. An important aspect is that it is necessarily involved in decoding the universe. In this respect, the discipline of astro-archaeology assumes some importance. This is the study of ancient knowledge of the heavens. It cannot have been the sole concern but the others – more to do with the Earth and the life around – have not left such traces as we can find in the form of massive structures that embody a knowledge of number and time cycles reflective of the pattern of celestial movements. There is also the concern of mind with decoding itself. This we can only surmise from the great wealth of ancient myth which has been tapped in the twentieth century as a major source of insight into mind itself.

Decoding the universe becomes simply coding, which is translation from one form to another, and becomes the basis of encryption and what has been called ‘ anticryption’ or the means of sending messages that can self-correct. This includes the possibility that humans of previous times have sent us messages with an internal logic that can enable us to decipher them. The idea of such an internal logic requires us to treat all of human kind of all times as ‘on a level’, meaning that we share very specific attributes of mind, in particular what we call ‘reason’. It is only fairly recently that we stopped treating earlier humans – or even contemporary people of other cultures – as inferior and lacking in reason. It turns out that it is actually the assumption of equal rationality that enables communication between time periods, regions, etc. and indeed underpins dialogue of any kind. It is the equivalent of the cosmological principle that underpins physics, which says that the laws of the universe should be the same at any time or place.

Understanding the time line of human history involves being aware of how it is being looked at. The usual experience is of ‘looking back’ over the past. When this is the case, we are bound to make a distinction somewhere between us-now and them-then. We know there was a time when there were no cities, or a time when there was no farming, back into a time when we would say there was no language, or even bipedal locomotion. We articulate the time line into sections, however fuzzy. If the fuzziness is seen as small, there is a vista of a radical change, a revolution. If it is large, there is a gradualist or ‘smeared’ model as in the well known parable of the frog boiled to death by raising the temperature of the water slowly. The story is not so trivial in this context. Because the issue is of whether when it comes to human history the change is noticed by those involved at the time.

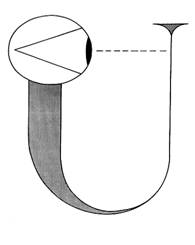

It is strange that ‘revolution’ has come to stand for a sudden change in the state of things, a turning upside down. The obvious and original meaning was that of going around a centre, as the planets make their revolutions around the sun, or the earth revolves around its own axis. In this sense it means recurrence, or repeating the same pattern, going back along the same path. The meaning of the word somehow managed to evolve to contain both senses of return and sudden change and it is worth while visualising this meaning. In terms of planetary motions, the planets are constantly falling towards the sun while at the same time serenely sailing around it in constancy. If we imagine a circular path broken into discrete chunks, then each chunk marks a change of direction. And, if enough of such changes are made then it returns into the same direction.

The thinking that breaks the path into chunks is just an approximation to grasping the continuous flow of the process. This thinking also chooses a reference point, a start and finish (see the small circle in the diagram). As far as the sense of history goes, this point is liable to be ‘now’ because our own time must always be significant in that we exist now. The location of our own now in a major time cycle is significant. Fuyukawa’s presumptuous ‘end of history’ places us at the major turning point. For those with some sense that we have a ways to go, we would be placed earlier on in the complete cycle.

All this simply means that the shape we give to the time line of human history will be influenced by our view of the future as much as the past. It is a relativistic eschatology, our view of where we might be going, without having to make it a final destination. It is a reasonable extrapolation to presume that the interval separating us from ‘early man’ may be repeated into the future, but paradoxical in that the future to be really significant cannot be the same – but we can only project what we know.

There is also the ineluctable ‘arrogance of the present’ which feels itself as more conscious than the past – in this case, due to the assumption that only now has human kind become aware of its history! This is in contrast with the view hundreds of years ago that the future of humanity had been mapped out from the beginning. It is a salutary thing to realize that the greatest genius of science, Isaac Newton, spent most of his life studying the books of prophecy to calculate the coming of the anti-Christ. Besides thinkers like Bacon who looked forward to a new Eden there were many who felt the last days were immanent.

It is intriguing to remember that we trace ourselves back into the past through three main media – written words, as in ‘history’ as such – artefacts, which extend into ‘prehistory’ – and genes. Between words and artefacts might be placed ‘oral history’ and myth (the fossil form of living memories) and also art, while between artefacts and genes are the bones of early hominids. Even two or three hundreds of years ago, all we had to go on were the words of ancient people which, in Europe, amounted to the ideas of the Greeks and Jews.

The punctuation of history – in terms of changes of direction, critical moments, beginnings and endings – is of course related to our perception of what is significant. It is a measure of ourselves (contra Alexander Pope).

In the diagram here, the items on the left are of the past and those of the future are on the right; the black region being a token of the present. It is but a sketch of a thought, but suggests not only a sequence of a past and future but other threads by virtue of its vertical dimension. The point of such a sketch is not to deliver a particular interpretation to the reader, but to intimate a way of reflecting on what we do in thinking of history. Just think of what could be put in the various places. How varied might this be?

For example, on the left, to put:

End of the last Ice Age

Birth of Christ

The Industrial Revolution

And, on the right:

The peaking of human population

Revolt against corporate control of resources

Climactic change

Different people, from different cultures and backgrounds, would think of different sets. For some, even ten years ago would pass beyond the ‘event horizon’ of significance while, for others, nothing less than the grand sweep of hominid evolution would count. The character of the moments chosen would vary greatly. There are more inward and more outward moments. The moments chosen reflect the moment in which the choice is made, or the ‘present’. The present is multiple in potential, determining itself by its selection of significance.

A prospect is then to consider moments in what we call past and future as themselves centres of perception and interpretation. There is then a network of communication, rather than just ourselves as the privileged agents studying the past. The picture can be extended to imagine people of different moments collaborating with each other. Such a vista is foreign to usual historical study but not so foreign to the contemporary world of physics.

The physicist Archibald Wheeler describes an ‘observer-participant’ as one who operates an observing device and participates in the making of meaning. He quotes Follesdal’s definition of the latter: “Meaning is the joint product of all the evidence that is available to those who communicate”. Wheeler’s view of the universe is that of, “world as system self-synthesized by quantum networking” and he gives a cosmic overview:

“We today, to be sure, through our registering devices, give a tangible meaning to the history of the photon that started on its way from a distant quasar long before there was any observer-participancy anywhere. However, the far more numerous establishers of meaning of time to come have a like inescapable part – by device-elicited question and registration of answer – in generating the ‘reality’ of today. For this purpose, moreover, there are billions of years yet to come, billions upon billions of sites of observer-participancy yet to be occupied. How far foot and ferry have carried meaning-making communication in fifty thousand years gives faint feel for how far interstellar propagation is destined to carry it in fifty billion years.” [In Complexity, Entropy and the Physics of Information ed. Zurek, Santa Fe Institute, p. 14]

‘Signals’ from the past reach us in ways dependent on what they travel through and what we are able to detect. Who would have known that the discovery of radioactivity in the early twentieth century would result in a method of dating? This illustrates what it means to have a ‘registering device’. But, it is not only a matter of some machine or other, because there needs to be a system of interpretation – otherwise, measurement is not meaningful – and this means a corresponding theory or way of seeing. We might begin to realise that we have barely started to ‘communicate with the past’.

Wheeler’s perspective suggests that ‘what is’ develops through observer-participation. Thus the past is not ‘just that’, something completely accomplished, but is becoming what it is through us; just as we are becoming what we are through future generations. Thus, the articulation of history evolves and cannot be anything fixed once and for all.

Contrasting with this vision is the model in which we consider all life – and human life in particular – to have been linked into the cycles of planetary phenomena. These cycles provide the basis of an ‘objective’ punctuation of time. How they are seen from Earth reflects into how they govern or measure events on Earth. That is, they are in some way related to a kind of perception.

The influence of the diurnal cycle is pretty obvious, because it is so clearly reflected in the rhythms of plants and animals. The monthly cycle connected with the moon is well attested. The yearly cycle gives life (in most areas of the globe) its seasons. It is not unreasonable to suppose that there are other cycles still of longer and longer duration that can have discernible effect on life on earth. These extend into major events such as Ice Ages and periods of catastrophic extinction of species. Climatic change has measurably influenced recorded history, as in the changes the drove the nomads of central Asia out into their ravaging conquests. At this stage in our knowledge, we do not know to what extent such events as Ice Ages relate to planetary cycles – or to the situation of the sun, our star, in relation to the spiral arm, for example.

What we earlier called the ‘perception’ of the cosmos by life on earth (an idea of Gurdjieff) is evidenced by the changes of fate of particular species that rise and fall, just as the health of coral reefs today inform us about the state of pollution in the oceans. There is a continuum from the major cycles of change possibly associated with our position in the cosmos to the ‘signs and portents’ that were the concern of our forefathers (even perhaps into the present day, as in the fairly widespread speculation about the Mayan ‘prediction’ of crisis in 2012). This was no simplistic ‘astrological prediction’ but an assessment of the nature of the times.

History is seen as punctuated by crises. A ‘crisis’ originally meant the decisive turning point, as in the course of a disease. Many such words deriving from the Indo-European root krei relate to the notions of judgement and discrimination, and hence to punctuation. If there were assessments of moments of crisis based on celestial observations these need not have assumed any definite form or result. As many of us today have come to feel, all that we can predict is that what is going to happen is not predictable. And it is this that may be called the real substance of a crisis.

The perspective of the emergence and evolution of life as coupled into planetary or other cosmic phenomena can be entertained at least as possible; but it has to be related to the increasing ‘inner autonomy’ of living forms. The situation might be conceived of in terms of simple ideas of mind and body, where the mind must be in one sense independent of the body but, in another, a reflection of what it can do. In other words, in human history we have assimilated the cycles of time into ourselves in creative ways but still they are there. As Freud wrote:

. . . man’s observations of the great astronomical periodicities not only furnished him with a model, but formed the ground plan of his first attempts to introduce order into his life.

Though this was never spelled out by him, Jung might well have discussed that cycles of time were embedded in what he called the collective unconscious and even that this unconscious was ‘made’ from such cycles. Though the Jungian corpus emphasises images as its medium of explanation and means of translation between conscious and unconscious, a more powerful reference might be to music. It is no accident that Kepler sought the ‘music of the spheres’ as an expression of the angelic intelligence and this was a subtle but no less real influence on his discoveries of planetary laws. Such ‘music’ is the basis for divination, such as in the I Ching where the mood of the moment is paramount.

The realm of divination is related to that of synchronicity and coincidence. Schopenhauer was a pioneer in proposing that there were two kinds of connection:

Coincidence is the simultaneous occurrence of causally unconnected events – if we visualize each causal chain progressing in time as a meridian on the globe, then we may represent simultaneous events by the parallel circles of latitude – all the events in a man’s life could accordingly stand in two fundamentally different connections.

Such an idea raises the possibility that events in different parts of the earth could be in accord, signifying a coincidence of mind, and allowing us to suppose that there could be a global history in which time cycles are synchronised across the earth. This mind would be a form of higher intelligence, because it is not an aggregate of separate minds interacting externally through evident physical means. There have been many speculations of this kind, including those of Rupert Sheldrake’s morphogenic field. Jung’s collective unconscious signifies something of a similar nature.

Time cycles raise the question of what defines the equivalent of ’12 midnight’ – or where do they start? The intersection of human mind with cosmic pattern is all important. When does it define this as happening? The western world still persists with the dating based on the presumed birth of Jesus Christ, a moment when Christians believe God came to Earth. This was to some degree presaged in the Jewish tradition which claimed to record at least ‘transactions’ between God and men, such as the Covenant. It is, to most modern people, just an arbitrary attempt to marry mythological and physical time.

‘Thus it began’ is a most tremendous idea. It reverberates down the ages to our contemporary presumption of a big-bang starting off the universe! It is the ‘x marks the spot’ of history.

An intriguing interpretation of the Incarnation is that time ‘goes’ both backwards and forwards from the birth of Christ. This can be extended to develop the idea that the ‘beginning’ moment is created from a moment in its ‘future’. A version of this is derivable from astro-archaelogy, which has hypothesised that maybe more than 10,000 years ago humans realized that the orientation of the poles of the Earth’s axis moved relative to the ‘fixed stars’ in an arc that takes almost 26,000 years to complete – a Great Year. About 17,500 years ago the plane of the ecliptic (imagine extending the circle of the equator) and the axis of the Milky Way (the way we see our own galaxy) were coincident, but since that time have deviated more and more. According to one interpreter, this gave rise to the idea of a separation between time (ecliptic) and eternity (Milky Way) and thence the need to find a ‘way home’ or a path to heaven, culminating in the image of Christ as nailed on the cross, that is suffering the consequences of this separation, as symbolised by the horizontal of time and the vertical of eternity.

If Wheeler’s idea of observer-participants holds then such speculations are reasonable and mark a significant coincidence of physics with mythology! Yes – we make the punctuation of history. And, yes – we build on something really ‘there’. It is a remarkable fact, as we have noted before, that Newton devoted much of his later life to unravelling the time cycles of prophecy. Newton is looked at as both the greatest harbinger of modern science and as the last of the alchemists and magicians of yore. His lifetime of enquiry brought together major threads of human thought.

It is still largely unrecognised that right into our contemporary era scientists have combined two complementary perspectives. In the one, the universe is a great machine, the workings of which are defined by localised interactions. In the other, it is seen as a holistic system exhibiting the hallmarks of intelligence. Today, it is the physicist (at least, some of them – Bohm remarked to us that most contemporary physicists are no more than technicians) who is at the forefront of enquiring into such things as ‘free will’ and ‘meaning’. Wheeler proposed that the universe was a great meaning circuit, an idea that gave rise to the image we showed at the beginning of this section. Any whole picture – or picture of the whole – must take account of our role of making pictures.

As we look back at that moment 70,000 years ago we are seeing ourselves. It must be noted however, that Wheeler’s picture leads us to think in terms of some kind of ‘interaction’ between observer-participants, rather akin to the previous picture of interactions between insentient particles. He proposed a model based on a game in which a definite object or word is established by a group the members of which interact by means of questions to be answered digitally as yes/no. This makes language all important; and it is not surprising that one of the most difficult questions to be answered is when, where and how language first began. The global mind has a basis in language and language ‘itself’ may turn out to be a most likely candidate for the ‘body’ of higher intelligence. The myths of the gods entering into human life might be seen as moments in the development of the capacity of humans to articulate the world. This would correspond to the evolutionary ideas of Wallace who insisted that the arising of human beings marked a moment when a different principle of existence began to operate.

When people enter into dialogue they may discover the presence of ‘something else’. In psychoanalysis, this is called ‘the third’ that comes into play when the dyad of analyst and patient becomes whole. There is no sense in considering this to be either prior or posterior to the interaction, because that would be to punctuate the time in an artificial way. As T S Eliot put it, history is a pattern of timeless moments.

Note

Since this was written there came to my attention the recent discovery of two major candidates for punctuation, concerning mutations in the human brain. One is said to have occurred about 37,000 years ago and the other, about 5,700 years ago. At present, there is no understanding of what these changes might have meant for us. The punctuation of human history derives from a variety of factors. Some of them are, like the ones mentioned, genetic. Others might be climatic. There is the possibility that some are due to human creativity and invention and changes in the social order. It is an open question whether there are or not punctuations that come from an intervention from another level still invisible to us, though perhaps faintly echoed in religious literature.

‘God’ is a catch-all word for all that we do not understand, which is on the fringes or beyond what we can be aware of. The postulate of my writing is that it is essentially to do with what can be aware of us which, of course, includes ourselves to some degree. This supposed awareness may be thought of as being inversely reflected in us in the ‘awareness’ that governs our physical existence. A useful simile is given in the idea derived from music of over and under tones. If we ascribe a tone the value of 1 (representing our kind of awareness) then the over tones are the multiples 2, 3, 4, etc. of it and the under tones are the fractions ½, 1/3, ¼, etc. of it. The over tones relate to ideas of ‘cosmic consciousness’ and the undertones to ‘incorporated consciousness’ such as that of a cell or gene. In a telling explanation, Gurdjieff stated that when we really understand any ‘cosmos’ or whole, we penetrate into both the higher and the lower cosmoses in relation to it.

The musical metaphor enables us to see how it might be possible to think about such things as evolution and history on a canvas that is far wider than can be encompassed by the restricted view of most historical interpretations. It does not require, however, any naïve view of higher intelligence as a set of beings floating around and doing things to us. Higher intelligence is operative simply because there is a ‘sounding’ of greater and smaller events in the sounding of our own existence. History is reverberation.