Structual Communication – An Introduction by Anthony Blake

This method was developed

by John Bennett in the late 60’s and applied to secondary education and, eventually,

to management training. In later years, it was simplified and modified to create

a method of group discussion that is, today, used in management circles. Arie

de Geus mentions it in his influential book ‘The Living Company’ though its genesis

is not recorded there.

In this introduction,

we make use of ideas that are to be found in the separate articles on Mental Energies

and Systematics.

Structural Communication

has evolved into logovisual technology* and has turned out to have wide-ranging

application far beyond the relatively narrow concern of the early days with teaching

in schools. It has even evolved beyond the restricted management applications

that were developed over the last twenty years. This is very much ‘work in progress’

and we can only indicate possible lines of future development.

Logovisual is a proprietary name owned by CMC, the Centre for Management Creativity,

UK. The information concerning logovisual technology should not be used without

permission.

“The data in

any given system may be recognised by everyone as the being the same. What differs

is assessment – ‘the art of handling the same bundle of data as before but placing

them in a new system of relations with one another, thus giving them a different

framework’ (to use the words of Butterfield). Nature herself builds up structures

in this way. Aristotle points out that ‘matter . . . can never exist without quality

and without form’. P. Weiss observes: ‘Take a gene out of an organism and it has

no more meaning than a particular set of cards has outside . . . a game of poker

or bridge. Both information value and function are context dependent.” Emilios

Bouratinos

THE METHOD

Understanding

Structural communication began in research into

learning that involved understanding rather than knowing. It is the kind of learning

that includes the ability to interpret new situations in terms of principles,

or to design solutions to complex problems. It is the kind of learning drawn into

play when people enter into mastery of a subject. It is the synthesis of theory

and practice, being able to see the wood for the trees and making complex judgements.

Mental Energies

In

Bennett’s own terminology of ‘mental energies’, this kind of learning involves

‘consciousness’ as opposed to the more basic reactional awareness that he called

the ‘sensitivity’. Consciousness is able to ‘see the whole’ and not get lost in

the parts. It is able to entertain alternative views of the same situation and

consider them together. There are four ‘mental energies’, including the ‘automatic’

that operates below the threshold of our awareness and the ‘creative’ that operates

above this threshold. The model provides a useful descriptive framework.

Creative

Sensitive Conscious

Automatic

Sensitivity deals

in parts, while consciousness deals in wholes. Creativity brings something new,

while automatism repeats the old.

Reading

Further to this concern Bennett and his

co-workers made experiments in levels of consciousness involved in reading. It

was found that we engage with a given text at various levels of mental energy,

fluctuating from moment to moment. This meant that there were (according to Bennett’s

model) four distinct kinds of reading:

1. automatic

level – reading without any awareness of what is read – the words are there but

they are not ‘meaning’ anything

2. sensitive level – reading that registers

the meaning of the words in terms of the network of associations the reader has

– the reader can verify he is reading correctly

3. conscious level – the reader

is able to separate his own set of meanings from that of the author and able to

compare them – this is the level of understanding at which he can ‘meet the author

in dialogue’

4. creative level – the reader transforms what he reads into

a deeper meaning than either he or the author had before

If

we were able to sustain reading at the conscious level, structural communication

would be superfluous. Gurdjieff pointed out to his pupil Ouspensky that he ‘could

not read’ – even the books he had written himself. This meant that he was unable

to read consciously. Needless to say, it is often the case that what is being

read is not even at the sensitive level!

Bennett’s

position was that consciousness could be evoked by appropriate challenge. This

meant that some task was created that could not be met by an automatic response,

nor even a sensitive one (that is, a ‘reaction’). The studies found that even

well-educated people could not refrain from reacting to what they read, which

tended to obscure the insight available from the text. Like and dislike were tyrants.

Hence there appeared a need for some artifice by which readers could be challenged

in such a way that their usual reactions were suspended, making them capable of

learning at a conscious level.

Tutorial

This

kind of learning was taken to be represented in the small group tutorial. In the

tutorial, the students do not simply learn to recite information and practice

techniques – the very way they think is challenged. As the tutor and student converse,

the tutor does not simply ask questions and tell the students whether they are

right or wrong; he involves them in a dialogue that broadens their grasp of the

subject. Whatever the students come out with, they are challenged to go further.

Bennett’s aim was to simulate the conditions of the

small group tutorial in a way that could be programmed in advance and administered

at a distance without the actual presence of the tutor.

Common Language

His first breakthrough was in

seeing that there needed to be a common language to interface between tutor-at-a-distance

and student. In the small group tutorial, the students have to acquire a working

language in order to enter into dialogue with the tutor. They must know what is

meant by technical terms – such as ‘entropy’ in physics – and also by references

to events – such as ‘Henry VIII’s formation of a new church organisation’ in Tudor

history. They must have ‘read up’ about such things. For any given topic there

will be a ‘universe of discourse’ that tutor and student must share, even though

the tutor’s knowledge will be far more extensive.

Coupled

with this insight was the realisation that such a working language could be constituted

out of a set of discrete elements, each of which represented a key piece of information

relevant to the universe of discourse. For any given topic, about twenty or so

such items were found sufficient to give an adequate working language. A useful

way of thinking about these items is as ‘molecules of meaning’ – ‘molecules’ because

they could be fitted together to make larger wholes supporting interpretations,

designs, etc. Because the working language was to be composed of a set of MMs

(molecules of meaning), they needed to be of much the same type, or on the same

level of abstraction. To illustrate the point: the method came to be used in the

analysis of case studies in management education, when the working language was

composed of facts pertaining to the case.

In broad

terms, any text can be reduced to a set of MMs that contain nearly all the information

it contains. If we know what the MMs mean, then we know the text and what it is

about. This is the first level of learning (at the ‘sensitive’ level).

Sub-sets

The second breakthrough was to realise

that we could ask questions capable of being ‘answered’ or responded to in terms

of a selection of a sub-set of MMs from the total. A crude but useful analogy

is with a court of law in which the same evidence is used by both sides of the

dispute to argue different points of view. Prosecution and defence will select

evidence to make their case in different ways. What is minimised or dismissed

by one side can be emphasised and made significant by the other. Thus, the same

MMs (supposedly ‘facts’) are given different values according to point of view.

In the simplest form of structural communication,

the author-tutor would create questions such that he could programme the system

to detect understanding and misunderstanding by means of tests of inclusion and

exclusion. He gave meaning to sub-sets of the MMs in terms of relevance to questions.

Say he wanted his students to express the essence of the second law of thermodynamics.

If they failed to mention entropy then they were sure to be missing something

important out. On the other hand, if they included something like specific heat

they were also missing the point, because it is basically irrelevant. So, for

any question created by the author-tutor, he could divide the MMs into two or

three sub-sets. One set would consist of those factors that should be included.

A second would consist of those that should be excluded. There could be a third

set of MMs that were indifferent either way.

Diagnostics

But

this can be made as complex as one likes. There will be some MMs that are more

important than others, or absolutely essential. Others could be relevant but of

lesser importance. Similarly, there could be MMs that would demonstrate serious

misunderstanding and others that would only indicate a small confusion. More than

that, there could be MMs that had to be considered together as a whole. For example,

the second law of thermodynamics does not only indicate an increase of entropy

in any change but also requires the understanding that this applies only in a

closed system. The one without the other is inadequate. So, we could also seek

to test for total inclusion of the essential items and allow for only partial

inclusion of secondary ones.

The testing of inclusion

and exclusion was conducted by a series of diagnostic tests. According to the

result of the test on the student’s response, so the author-tutor prepares a corresponding

comment. This need not simply tell him whether he was ‘right’ or ‘wrong’. It could

give him or her further food for thought and a chance to try again. The student

is left ‘suspended’ giving him or her opportunity to make another step.

In

this way, the student would be taken through a series of ‘moves’, learning by

doing.

Structure

From

about 1967 to 1970, the method was applied to teaching chemistry, physics, mathematics,

history, leadership, case studies, etc. first in schools and then in management

training. The educational application followed a set pattern:

INTENTION

– stating the purpose of the work

PRESENTATION – giving descriptive information

on the topic

ARRAY – A set of twenty or so MMs drawn from the presentation

arranged without any obvious order

INVESTIGATION – usually four questions

calling for interpretations that could be expressed by a subset of the array

DIAGNOSTICS – the logical tests of inclusion and exclusion

COMMENTS – the

further statements relevant to the outcomes of the tests

OVERVIEW – a statement

returning to the intention and articulating the basic principles of the topic

Flatness

to Depth

This seven-fold scheme proved an excellent

vehicle for the method. It allowed the student to explore the inner structure

of the topic and come to see how the MMs related to each other in deeper and more

subtle meanings than those that appear on the surface. The ‘flat’ surface of the

array acquired depth. In a qualified sense, the student gained his or her understanding

by doing something with the information with which they were provided.

The

disorder or randomness of the MMs in the array left it up to the student to discover

the ‘hidden order’ that lay behind it. The step of understanding involved may

be likened to how an ‘autostereogram’ first appears as a random set of dots and

then reveals an image in three dimensions.

The work

of the author-tutor was considerable. Take the creation of the questions. These

had to be designed, as far as possible, such that every MM was involved in at

least one of them as an ‘essential’. This could be extended so that every MM played

a different role in every question: strong inclusion, weak inclusion, strong exclusion

and weak exclusion.

THE NEXT STEP

Creativity

The

essential nature of the method hinged on having a ‘flat’ interface – the array

– in which every MM appears on the same level as any other. The interactive process

was designed to enable the student to share in the ‘depth’ of meaning behind this

surface.

It became obvious that the process of constructing

a piece of structural communication was far more demanding and rewarding than

just interacting with it. This is because the construction required creative energy,

postulated as above consciousness. The author-tutor had to act on the creative

level, so that the participating student could act on a conscious level. The conscious

level, in its turn, could serve to organise the knowledge acquired at the sensitive

level.

If a first level learning takes place in sensitivity,

then a second level learning takes place in consciousness and a third level in

creativity.

Research began into how it might be possible

for students to engage in the construction process and be ‘creative’. This meant

that they had to be involved in creating the array of MMs and also in the generation

of questions as well as their interpretations. This work was led by Tony Hodgson,

a student of John Bennett.

Magnetics

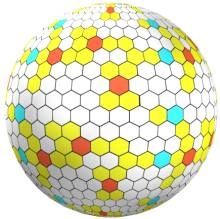

A

move in this direction was made possible by means of the device of magnetic hexagons

that could be written on and affixed to a metal-backed white board. One such technology

is called MagNotes. Such hexagons could be placed and removed, written on and

erased. A group meeting in discussion could work together to build their own common

language. According to circumstance, they could be as precise or vague in their

terminology as they cared to be.

In relation to their

array of MMs, the group could raise questions, such as: ‘What are the factors

that have a bearing on our mission?’ or ‘What represents the obstacles to change?’

and so on. In response to such questions, the group could select and ‘cluster’

the hexagons. Hexagon shapes were used because they fit together well in clusters.

If different people had different views, then they could discuss the issues involved

by reference to their common language. This meant that they could be more objective

in their exchanges. In a verbal conversation, even supported by flip-charts, there

can be no common language, so confusion is likely. By having the exchange based

on moving the hexagons about into different clusters, they could more easily see

how each other was thinking. It also involved the participants in a physical activity

of movement and manipulation that facilitated learning by engaging more of the

person.

By this means, the essentials of structural

communication were made available to the participant for him to work at as he

or she pleased. The main application was to groups, because in this way a variety

of interpretations was made available to all. The creation of the working language

required consensus but the investigation brought differences to the surface.

Facilitation

Needless

to say, the working of this method very much depended – and depends – on the quality

of facilitation brought to bear. It is more than useful to have present someone

who is versatile in the techniques. Here we have a paradox: the same system that

enables people to find out for themselves enables someone of understanding to

better educate them. The method is a powerful tool in providing an interface between

people identified with partial views and someone who is not. Below, we refer to

Chris Argyris’ statement of four kinds of mentality, which needs to be mentioned

here because it supports the point we have made. In this scheme, the fourth mentality

– ‘structural’ – is capable of navigating between a variety of subjective views

because it is operating in more dimensions than they are individually.

It

has, therefore, become a tool for consultants that is becoming more and more used.

The master of facilitation can be said to work in ‘unitive energy’, which has

been called by Patrick de Mare koinonia or impersonal fellowship (also see later).

This fellowship is more than a feeling since it engages the capacity to see the

‘sameness’ in diverse views.

Meditation

Meditation

is mental concentration and this can be greatly facilitated by the technique applied

by a single person to examine his or her own thoughts. We are used to relying

on the ‘screen of the mind’ – the sensitive energy according to Bennett – to display

to ourselves what we are thinking, assisted perhaps by writing things down. Structural

communication provides a complex mode of display that enables us to see more of

our thinking at any one time than is possible by either – internal or external

– of these means. We could also say that structural communication goes some way

towards displaying the holistic or right-brained view of things.

There

are single-user forms of magnetic hexagons by which we can write down what we

know and then examine the meaning of combinations and connections of what we know.

Being able to do this in a two-dimensional way is a great advance.

TECHNOLOGY

AND APPLICATIONS

Systemaster

The

engagement of structural communication with information technology began in the

early days. Working in collaboration with the then GEEC company, an electro-mechanical

device called the Systemaster was invented. This was in an era before the pocket

calculator and well before the wide-spread use of PCs. The Systemaster machine

could be ‘programmed’ to search for inclusions and exclusions in the student’s

response. This response was made by keying in the numbers (1 to 20) attached to

the MMs. This enabled the information handled by the machine to be very simple,

involving only these numbers and not the content of the MMs themselves. Needless

to say, the device was cumbersome and far from user-friendly and never came into

use.

Internet

In

the year 2000, structural communication was adapted by Jason Joslyn (in collaboration

with Anthony Blake) for use on the Web through the technologue developed by him.

By this time, the technique of using magnetic hexagons had acquired its own software

(one version is called Visual Concept). This was partly driven by the wish to

have a permanent record of the structures evolved during discussions. It was also

needed for people wishing to follow up an investigation with each other at a distance.

Organisation

The

full application of the original system is eminently suited for highly structured

subject matter in which a variety of modes of understanding have come to be accepted.

It is less suited to a free exchange of views. The kind of ‘random’ exchange that

manifests over the Internet does not encourage the reflective and co-operative

work of establishing a common language. It is not impossible, only very difficult.

Work is in progress to realise this potential.

The

organisation of knowledge has become a burning issue. Structural communication

affords a way of communicating in depth that lends itself to this work

Systematics

Here,

structural communication links with systematics (see the separate article under

that name). In systematics, we strive to make clear which system we are working

in. A system is defined by means of the number of terms of which it is composed.

One person may be concerned with relationships – and hence the triad – while another

may be concerned with order – and hence the tetrad, and so on. If they do not

know what each other is about, they can mis-communicate. However, if they are

working with a common set of MMs it is readily apparent whether they are working

in triads, tetrads or whatever because they are selecting three MMs or four MMs

respectively.

Texts

Liz

Borreden – also a one time student of John Bennett – has produced a pioneering

piece of work by using a software based on the technique of using magnetic hexagons

to analyse the structures of meaning in a book on ‘mentoring’. Her conclusions

make use of triads and it is clearly visible what her intentions and modes of

thought are. This has led us to suppose that we might consider writing books in

a form of structural communication right from the start. Such a ‘book’ could then

become available on the web in suitable form. It would fulfil the now largely

lost promise of hypertext.

All such techniques are

artificial means made necessary by the fact that we are incapable of sustaining

reading on the conscious level. It is significant that most people find the suggestion

that they cannot read offensive. Because of this, they will tend to refuse to

adopt the disciplines offered and reject them as unnecessary and confining. Such

reactions are typical of the sensitive level. New methods are only adopted by

people who have seen that they are needed.

Logovisual

Technology

The various ventures that have stemmed

from the early days of structural communication have now converged into the realisation

of a diverse genus or method called logovisual technology.

The

idea of logovisual technology has emerged out of a collaboration between Anthony

Blake and John Varney, Director of the Centre for Management Creativity (CMC)

We have come to realise that there is a whole genus of methods and inventions,

inclusive of such CMC products as MagNotes, and ranging beyond them. We think

the recognition of this genus of methodology is important and will serve to accelerate

and spread the use of such methods. Most significantly, it might enable practitioners

in different fields to see what they have in common and managers to understand

that there is a shift in our working language and culture taking place.

The

term ‘logovisual’ refers to ‘meanings made visible’. Logovisual technology is

anything that puts meanings on display so that they can be handled. The technology

can be based on very simple means – such as the ubiquitous post-its – but it can

extend into use of computer software. Such technologies are now being introduced

as part of such methods as TRIZ, mind-mapping, problem-based learning, Metaplan,

scenario planning, structural communication, and so on and involve artefacts such

as post-its, MagNotes and Visual Concept software.

The

essential features of logovisual technology are easy to define:

1.

Thoughts are turned into tangible objects

2. These objects can be displayed

and manipulated on surfaces

3. They can be combined, grouped, clustered, ordered

or otherwise arranged to reveal or express patterns

We

call ‘thoughts turned into objects’ molecules of meaning or MMs for short. The

pronunciation of MM – as ’emem’ – turns out to be the reverse of meme, which is

the technical term for a unit of meaning as in meme theory. Turning a problem,

a situation, a topic, an issue, or whatever into a set of MMs is the first crucial

step. The set of ‘molecules’ can then be selected from to build into more complex

wholes.

Imagine a board full of MagNotes – magnetic

backed hexagons written on. This is like a ‘knowledge soup’ and can be drawn upon

to make new kinds of knowledge. If a group has assembled the MMs, then it also

constitutes their common language. Though they might continue to talk and associate

ideas together, this is accompanied by and represented in the common language

by moving, assembling and structuring MMs – making the thinking visible. The term

‘knowledge soup’ suggests the metaphor of amino acids that can be assembled into

specific purpose proteins. It is highly significant that some recent trends in

computing science are towards physical biological processes and away from software

programming in the old sense.

Having the MMs on display,

so that they can be seen and handled, makes it easier to look for patterns. MMs

fit together as ‘opposite trends’, ‘relationships, ‘machines’, ‘cycles’, ‘structures’

and so on. Combinations of MMs can be used to capture new insights, diagnoses,

designs, etc.

Logovisual technology optimally involves

‘multiboarding’ – the use of three or more distinct display surfaces. These fulfil

the following roles:

1. Stores and displays the knowledge

soup: the common language, the pieces of the game play, the molecules of meaning.

2.

Brings selections from the knowledge soup into conjunction as systems of meaning,

or more complex wholes, as the investigation, working process or game unfolds.

3. Displays and records the synthesis of systems,

providing links with supporting documentation and illustration.

Board

2 can provide a ‘game arena’ allowing for the unfolding of a space of contention,

with contrasting views. Board 3 then represents a higher space of synthesis, in

which contention is resolved in co-operation.

The

metaphor of a ‘game’ is used because the MMs are just like pieces in a board game.

In a single-boarded version of logovisual technology, the MM pieces can be arranged

around the periphery of a white board and ‘brought into play’ by different people

making different selections and combinations to make their point in the centre

region. The interesting thing is that we can move from the more usual competitive

mode to a co-operative one.

Logovisual technology

is here to stay and will become more and more widely accepted as it enters into

everyday working practice. It need not be tied to any one specific method because

it is a tool or medium for people to use as they need just as pen and paper might

be. However, it promises a step in mutual understanding, because the very ‘shape’

and construction of our ideas can begin to be made visible to each other.

The

idea of logovisual technology is reflecting back into computer-based applications,

where we are looking for ways of applying technologue to allow for the colouring

of MMs to simulate the physical operations experienced by handling the more tangible

pieces such as MagNotes.

Logovisual Logosphere

OTHER REFLECTIONS

Dialogue

It

is more than curious that the number of MMs we came to use – about twenty – is

identical with the optimum number – according to Patrick de Mare – for a median

group. The size of such a group is determined by the requirement that everyone

can see all the others and be able to say something within the span of an hour

or so. In the same way, the array of MMs is such that a ‘reader’ going through

the structural communication process can at least ‘feel’ the mutual relevance

of every one of them with every one of the others.

As

in the dialogue process of the median group, the mutualities of the MMs break

up into smaller sub-sets, dealt with one after another. Still it is just possible

to attain a sense of the whole. This is because we allow consciousness to come

into play. There has to be an alert relaxation and atmosphere of trust.

Public

Forum

An application of logovisual technology,

in the form of hexagonal post-it notes, is being tried out in Burma. People get

together to discuss issues based on arrays of MMs that can utilise any available

surface – even curtains! In this application, we are seeing something of the same

nature as the public display systems adopted, for example, in China, where available

boards in parks or other public spaces can be used by the polis to post ideas

and formulations.

The idea of the ‘public space’

or ‘forum’ is well known but it gains considerably by having a suitable technology

that allows people to display MMs and arrange them in patterns. The simple means

of having tangible MMs that can be moved around makes a great difference.

Mentalities

Structural

communication may be nothing new, only a creative revival of something that was

widely prevalent amongst the learned centuries ago. In our present age, education

has sunk to such low levels that it is rare to find any example of structural

communication in it. In management circles, also in the 60’s, Chris Argyris produced

an important paper in the Harvard Business Review outlining his conception of

four modes of thought:

1. Black and white mentality.

There is only true and false, right and wrong.

2. Gradated mentality. There

are greys of more or less true, more or less right.

3. Relative mentality.

My view is mine and yours is yours and stem from our subjectivity.

4. Structural

mentality. We can navigate from view point to view point through understanding.

In

this scheme, mentalities 1 and 2 refer to the automatic and sensitive levels,

while mentalities 3 and 4 refer to the conscious and creative levels. Needless

to say, it is only the fourth kind of mentality that feels at home with structural

communication! This raises the question of how it is possible to bring at least

some of its wealth to people who seem to lack this fourth kind?

Art

Even

when we do not have clearly discrete units in the ‘language’ the same principles

apply. Think, for example, of a good painting. Though this cannot be crudely divided

into different parts, nevertheless there is a sense in which we feel every feature

of it as relevant to every other. Thus the good painting forms a whole. The same

applies to a good piece of music, or to a poem.

There

is no reason to reject structure in art, though this has been obscured in the

present commercial climate of the art world. If we go back to ancient and sacred

texts, recent studies have shown that they are highly structured, usually composed

of twelve to twenty ‘verses’ or parts, strongly cross-connected with each other.

Simon Weightman, another student of John Bennett, is currently showing that such

a structure exists in the great poem of Rumi called the Mathnawi. The superficial

audience will only register the text in a linear order. A more sophisticated one

– ‘in the know’ – will also register the inner connectivities – that is, in depth.

Thinking in Process

Once

one is used to a logovisual medium, it can become a natural part of any discussion

or investigation. In this mode, all that is entailed in the construction and execution

of the original structural communication method is brought into play. What emerges

is a complementary mode of thinking in which the discrete – MMs – is combined

with the continuous – the flow of talking. In scientific circles, it is common

to have both equations and free discourse combined together. The equations are

like MMs – and it is apparent that such MMs are selected, brought into play, combined

and altered as the conversation evolves. It can be all-important to be able to

register the various stages in the conversation as insights are brought to expression

and given form.

The dual-level nature of scientific

conversation gives it its power. The conversation is anchored on definitive elements

of meaning that are understood by all involved and give it a common base. It is

now being understood that this dual-level structure is the key to creative collaboration.

Naturally enough, this ‘thinking in process’ – even

though it can be conducted on table napkins! – is best served by having a number

of boards that allow for different spaces of work. Whole rooms can be designed

to allow for complex conversations, including having available PCs for the expedient

recording of significant stages in the discussion.

Even

without PCs (and appropriate software) the very nature of the display of MMs facilitates

memory of significant ideas. It is being found that the bare memory of a significant

combination can serve to remind the participants of what they were thinking in

making it. This is much more effective than trying to remember what was said in

the course of the conversation. We can therefore claim that logovisual technology

is making a new contribution to the recording of ideas. It is useful to note that

this facility resonates with the practice, centuries ago, of the art of memory.

ILLUSTRATIVE MATERIAL

A.

A Simple Example

To illustrate the basic method,

we will take some single words, all of the same kind, as our MMs and see what

they can mean in combination. These MMs are possible answers to the question:

What are the basic actions that make us what we are? This gives us our monad to

use a term from systematics, the world of our discourse.

The

question by which we generate the MMs can be called the ‘zeroth question’!

Other

questions draw out sub-sets to represent the ‘hidden’ organisation and meaning

of the MMs.

| Communicating | Moving | Breathing | Stilling |

| Seeing | Sensing | Expressing | Relaxing |

| Caring | Blending | Sustaining | Knowing |

| Attending | Visualising | Stopping | Making |

We

can now examine these in sub-sets to bring out the implicit structures of meaning

that are enfolded in them – to use David Bohm’s terminology – by means of a set

of further questions.

1. What reflects ‘awareness

in action’? The essential factors form a triad:

Moving

Sensing Visualising

This applies when we are simply activating our own

bodies. Another triadic interpretation:

Making

Knowing

Seeing

when we are concerned with interacting with

the world around us. We can see at once that the two interpretations correspond

to each other (they are arranged to show this) and that seeing and visualising

are linked, as are knowing and sensing.

2. What are

the key factors in participating in dialogue? There is a basic three-term system

lurking here:

Communicating

Caring Expressing

Communication

as in dialogue requires the combination of both caring for others and the power

of expressing oneself.

3. How can I ‘suspend time’?

Since this refers to something that is sustained, it is likely to be a tetrad,

thus:

Attending

Breathing

Sustaining

Stopping

There

is an exercise in which I bring my attention into my breathing and sustain it.

This can lead to the experience of time stopping. The breath is not stopped, but

any sense of change is.

4. How can I build up an

inner energy for my being? Again, this could be a four-term system, such as:

Stilling

Relaxing Blending

Making

If I bring myself into a stillness and blend

different energies in the containment of this stillness, then they make a new

substance that ‘feeds my being’ or my inner life.

The

illustration is worked out in a simplistic way, and we do not provide any ‘corrective’

diagnostics for less than optimal responses (or selections of sub-sets). Neither

do the groupings we exhibit overlap very much. In a more developed version, the

meaning of these sixteen words would be expounded upon and the ground prepared

for considering such questions. However, what we have shown should be enough to

give you some idea of how structural communication works. It should be easily

seen how this method gives depth to a communication. Even when the reader may

not be at all sure about what the author intends, the structure is rich enough

to evoke corresponding experiences in him or her and lead them into an active

contemplation of them.

B. Complexity in the

MMs

In our simple example, the MMs or elements

of the array were just single words. They can be far more complex. Here are four

of the MMs that were used in a structural communication text on Thermal Physics,

to illustrate the point:

the number of antinodes

fluctuations

spectrum a

coloured surface

in the range ![]() of

of

energy of

ionized often emits its

is ![]() gas

gas

complementary

colour

when heated

The array contained statements, definitions

and equations. However, in this universe of discourse, all could be taken as on

the same level. With such richly informative MMs, it was possible to discuss,

for example, how the photoelectric effect could be explained in terms of quantum

mechanics. The student could have the direct experience of adding ideas together

to make a greater whole. This was the kind of thing foremost in Leibniz’s ‘Universal

Calculus’ (see brief mention in article on Systematics).

Even

more complex MMs could be used. For example, in reviewing ‘The Foundations of

Wittgenstein’s Philosophy’ by Ernst Konrad Specht, we used an array composed of

twenty statements from Wittgenstein’s own writings (in the journal Systematics

Vol. 7, No. 2). We give some of them here (together with their numbers – see the

comment above on the Systemaster machine) to illustrate what we mean.

1.

Is it even an advantage 6.

The ostensive definition

19. . . . if things were

to replace an indistinct

explains the use – the

quite different from

picture

by a distinct one? meaning

– of the word

what they actually are

Isn’t the indistinct one

when the overall role of

. . . this would make

often exactly what

we the

words in the language our

normal language-

need?

is clear.

games lose their point.

The reader was

invited to do such things as find the subset [of statements from the array] which

illustrates Wittgenstein’s criticism of the atomic view. He or she could then

compare his assessment with Specht’s through a series of diagnostics and also

receive further commentary from another view than Specht’s.

The

more complex the MMs, the more subtle the interpretation of their combinations.

This example shows how structural communication is very much the same as reading

at a conscious level.

C. Example based on this

article

We can reflect on the ideas and experiences

expressed in this very article by means of a structural communication approach.

We will keep the MMs fairly simple. Of course, the selection of the MMs for the

array is somewhat arbitrary since we have no specific target audience. The rows

and columns of the array do not signify any order of connection between the MMs.

As we said at the beginning, their arrangement is deliberately random.

The

linear order of the text is followed by the ‘zero’ order of the array, and the

process of structural communication then reveals the integrative order of the

meaning of the text. We will not provide actual diagnostic test but some sets

of inclusion and exclusion from which they would be made.

| 1. Intention of communication | 2. Subsets of the array | 3. Modelling | 4. Meaning in depth |

| 5. Suspension of reaction | 6. Number systems | 7. Common language | 8. Computer simulation |

| 9. Group discussion | 10. Consciousness evoked through challenge | 11. Interpretation | 12. Works of art |

| 13. Points of view | 14. Atomic or molecular nature of MMs | 15. Reading with understanding | 16. [True] dialogue process |

| 17. Creativity | 18. Levels of mental operation [energies] | 19. Physical movement of the MMs | 20. Equi-value of all MMsin the array |

Question:

How can structural communication accommodate a variety of points of view?

Essential

technical points: 2 + 7 + 20 these form a group of ideas that underpin the technique

Ancillary points: 6 + 14 refer to the example of different people using different

number systems

Relevant points: 5, 9, 16 these are MMs that refer to the kind

of process involved

Misunderstanding: 1, 8, 12, or 19 show the point of the

question has not been grasped

Irrelevant points: 3, 4, 10, 12 etc.

Question:

What is the rationale for structural communication?

Essential

points: 4 + 5 + 10 + 15 + 18 it is to enable people to read with understanding

through a challenge that evokes consciousness and in the suspension of reaction

Misunderstanding: 8, 12, 19

Etc.

Overview

The

original venture of structural communication gave way to the invention of more

open-ended techniques and has, in recent years, metamorphosed into logovisual

technology. This is more of a medium of thinking rather than any set method. Anyone

who recognises the need to work at mutual understanding and co-operation can now

appreciate the value of this new medium.

A shift

in the paradigm of structural communication has come about. Instead of taking

the ideal case of the tutor and the small group, we are more into picturing it

as a creative game. The physical aspect of logovisual technology has come to the

fore. There is even work being done on making the computer interface more physical,

so that the concrete movements made by people using MagNotes can be simulated

in using a PC.

The medium is also being explored

as an aid to more effective conversation through email. Email exchange is bedevilled

by excess of words and the problem of keeping track of diverse and divergent lines

of thought. The indications are that once people have experienced the facility

offered them by the discipline of MMs and display in patterns, they can rapidly

become adroit in this new medium and use it as a matter of course in conducting

‘conscious conversations’. Research is being done into how to facilitate this

in the email domain.

The new units of meaning made

by combining MMs are called ‘toponomes’. The word ‘toponomics’ means the ‘rules

of arrangement’. A toponome is a combination of MMs that shows a pattern of meaning.

The concept draws heavily on our sister discipline of systematics. Once acquired

as a practice that has become natural and easy, the use of toponomes becomes a

familiar part of language. It is a part that encourages a perception of wholeness

and resonates with what has been considered as ‘sacred geometry’.

The original structural communication research

was documented in the journal Systematics Vol. 4 no. 4 and Vol. 5 no. 3 in 1967.

From this work, a series of structural communication textbooks were published

on topics including organic chemistry, Tudor history and Thermal Physics. These

‘study units’ were extensively tested in schools. Samples of some of them are

to be found on www.structuralcommunication.org. Management

case studies put into structural communication form by Tony Hodgson were published

in the Harvard Business Review.

Magnetic

hexagons and boards may be obtained from CMC – go to

www.logovisual.com – also

an equivalent software called ‘Visual Concept’. CMC is a management consultancy

and network developed by John Varney, yet another student of John Bennett.